WHERE PLAY IS SERIOUS BUSINESS

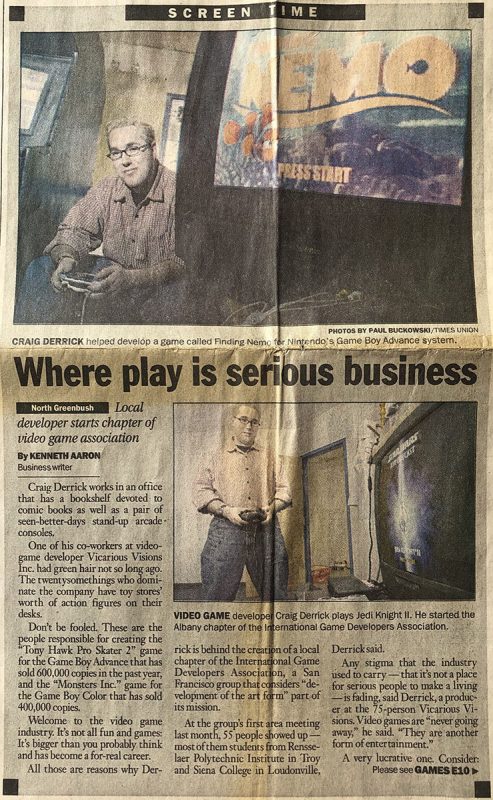

Craig Derrick works in an office that has a bookshelf devoted to comic books as well as a pair of seen-better-days stand-up arcade consoles.

One of his co-workers at video-game developer Vicarious Visions Inc. had green hair not so long ago. The twentysomethings who dominate the company have toy stores’ worth of action figures on their desks.

Don’t be fooled. These are the people responsible for creating the “Tony Hawk Pro Skater 2” game for the Game Boy Advance that has sold 600,000 copies in the past year, and the “Monsters Inc.” game for the Game Boy Color that has sold 400,000 copies.

Welcome to the video game industry. It’s not all fun and games: It’s bigger than you probably think and has become a for-real career.

All those are reasons why Derrick is behind the creation of a local chapter of the International Game Developers Association, a San Francisco group that considers “development of the art form” part of its mission.

At the group’s first area meeting last month, 55 people showed up — most of them students from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy and Siena College in Loudonville, Derrick said.

Any stigma that the industry used to carry — that it’s not a place for serious people to make a living — is fading, said Derrick, a producer at the 75-person Vicarious Visions. Video games are “never going away,” he said. “They are another form of entertainment.”

A very lucrative one. Consider: One trade group expects $12 billion in video game hardware and software to be sold this year; Hollywood films, meanwhile, brought in $8.4 billion at the box office last year.

“Gaming is bigger than it’s ever been,” said Marc Destefano, an RPI instructor who teaches classes in game design and game development. “Games are starting to be recognized as a legitimate art and a legitimate science, and it’s only going to get bigger and bigger.”

When he first offered the design class — which features lectures on arcade-classic “Centipede” and “The Sims,” a wildly popular game that lets players do things like go to work and cook — 50 people signed up in two days.

He enlarged the class to 100. And this semester, it filled again in two days.

Destefano is trying to institute a gaming minor at RPI. While schools teach programming and art and mathematics and cognitive psychology, the industry is looking for workers with some ability to comprehend all of those disciplines. “It’s about how to bridge that left brain-right brain divide,” Destefano said.

Making a game is not just about writing zillions of lines of computer code. Some of that is involved. But a walk through Vicarious Visions’ office in Rensselaer Technology Park shows that there is a lot more than that.

Some offices hold game designers who come up with the overall concept for a game. Others hold artists whose walls are covered with printouts of the various characters they’re working on. Others house programmers who make the characters do what they’re supposed to.

“An average game is at least 20 to 30 people on a team,” said Jason Della Rocca, program director at the International Game Developers Association. Some blockbusters are built by more than 100 people. And the trick is getting all those teams to work together and to understand what makes a game fun.

“That stuff doesn’t get built by robots,” he said. “This is stuff that’s created by artists and designers and programmers.”

The students who are ready to turn their game habits into jobs sometimes have to deal with a lack of understanding from their families. Ian Stead, a 20-year-old RPI junior, wanted to go to DigiPen, a school in Redmond, Wash., that offers a four-year degree in game-making.

“My mom — she couldn’t handle that at all,” he said.

Stead, who grew up thinking he’d be a comic artist, is happy for a local Game Developers Association chapter. “RPI isn’t really known as a school for game development,” he said. “Anything that can happen to make RPI be relatively known (in game circles) is important.”

Besides acting as a tutorial ground for potential game designers, the Albany chapter can serve as a destination for big-name industry speakers, said Vicarious Visions’ Derrick. When video game luminaries come East, they generally will address Game Developers Association chapters in Montreal, Boston or New York City — and Derrick said Albany makes a good middle ground where the big-city chapters can meet.

And he also wants prospective game designers to know the industry has a place for them even if they can’t code a lick.